Hyperfocus, scatterfocus: improving personal productivity and creativity with two modes of focus

Develop an awareness of consciously identifying where we're spending our attention.

Recently, I read a book called “Hyperfocus” on improving personal productivity. It introduced to me the concept of "attentional space." Our attentional space is limited, so we must consciously and reasonably use it – a notion I deeply resonate with.

The most important lesson I learned from this book is to develop an awareness of consciously identifying where I'm spending my attention and, when distracted, consciously pulling myself back to the task at hand; consciously making reasonable use of my attentional space; and consciously letting my thoughts wander to find good ideas that rarely surface during busy times, while also allowing my busy brain to rest fully.

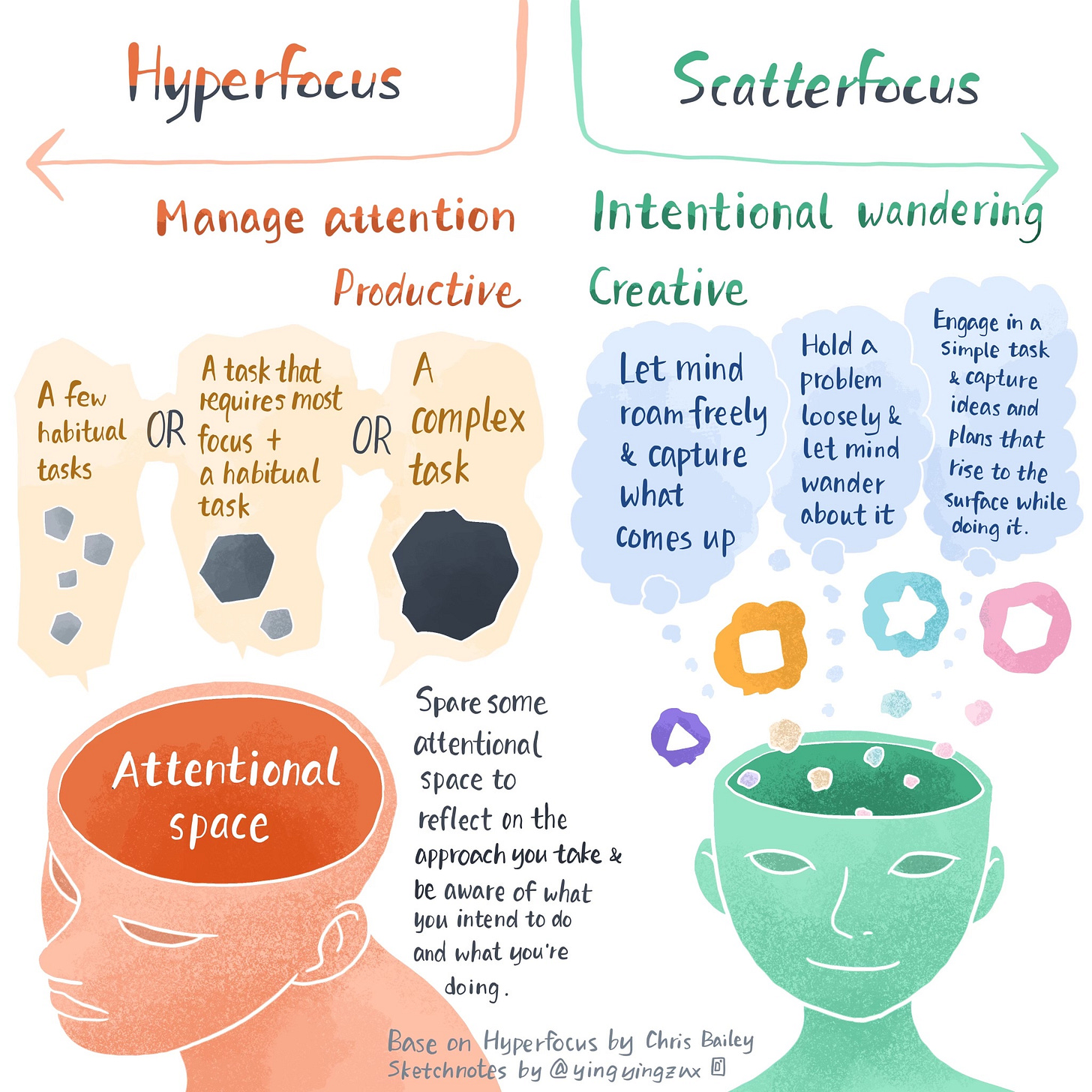

I sketchnoted my learnings:

The book is divided into two parts:

The first part focuses on hyperfocus, mainly discussing how to manage attention in a world full of distractions.

The second part focuses on scatterfocus, primarily exploring how to be more creative while continuing to manage attention and thoughts. I particularly enjoy this topic because both my work and hobbies require creativity. Although this part seems quite different from the first, they share many commonalities.

Hyperfocus

"Hyperfocus" refers to a state of intense concentration where a person enters a highly focused mode, fully immersed in their work. This part discusses how to manage attention in a world full of distractions.

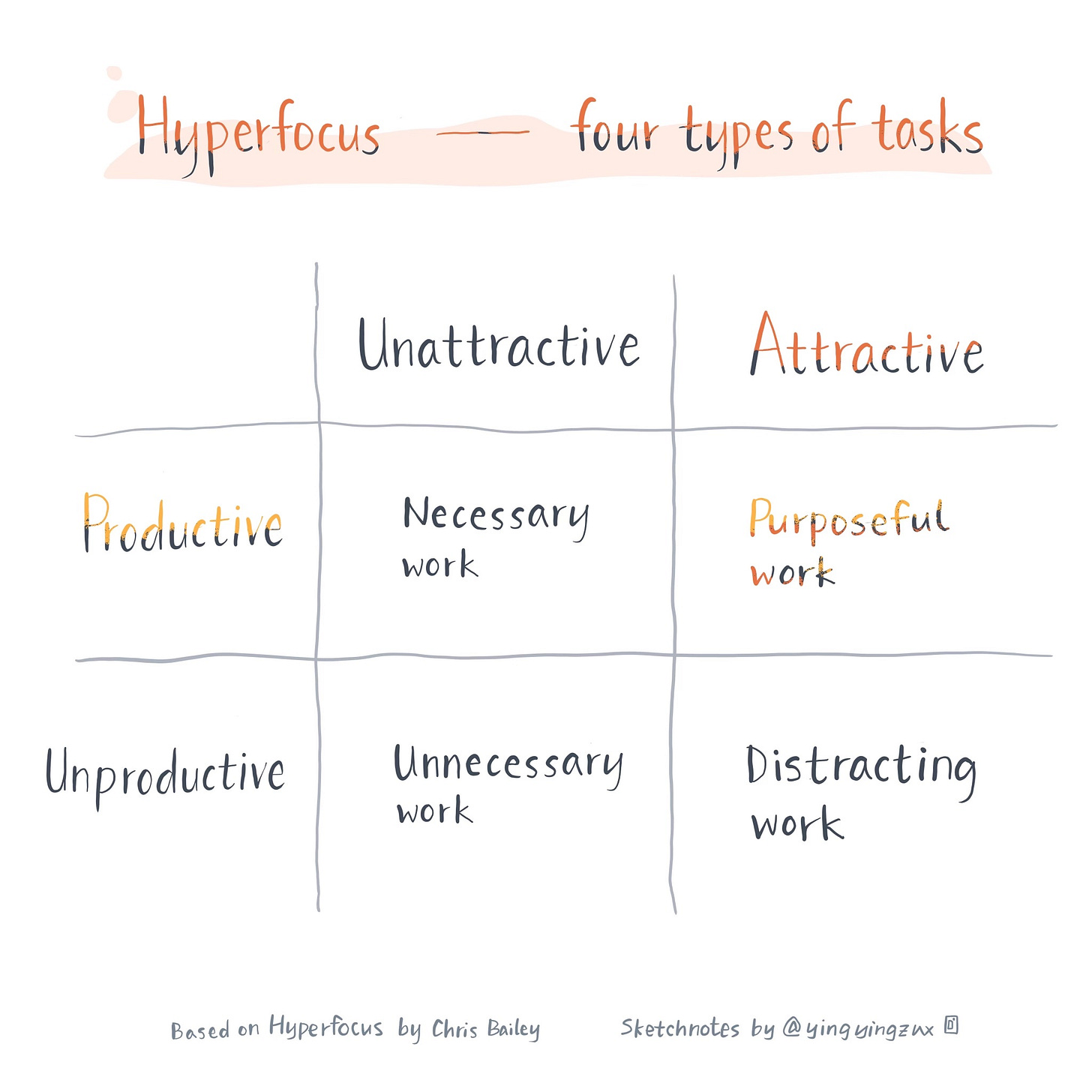

The author recommends that before we do something, consider:

Is this task productive (e.g., will it advance project progress)?

Is this task attractive (do you find it interesting), or unattractive (do you find it boring, difficult, or frustrating)?

Tasks can be divided into four types:

Unattractive but productive tasks are necessary, such as team meetings. Even if we lack interest, we generally have to complete these tasks.

Unattractive and unproductive tasks are unnecessary, like organizing documents in a drawer that haven't been touched for a long time. Often, we don't specifically allocate time for these tasks; instead, we do them when we don't want to do other, more important tasks – in other words, when procrastination strikes. Spending time on unnecessary tasks may make us appear busy, but the result is wasted time without accomplishing what we should be doing.

Attractive but unproductive tasks are distracting, such as checking social media, watching videos, chatting, and various activities that easily divert our attention. These tasks often provide little return for our time investment. Occasionally spending some time on these activities isn't a problem, but if left unchecked, we may find that all our time has been consumed by this productivity black hole.

Attractive and productive tasks are meaningful. When doing these tasks, we feel that life is fulfilling, and we enjoy the process. Few tasks meet these criteria. At work, as a designer, what I find meaningful is helping my product team build empathy for users and creating excellent user experiences through design. Outside of work, I also enjoy reading about these topics and attending related events.

Everyone's attentional space is limited. The more complex a task, the more attentional space it occupies, leaving less space for other tasks.

Some minor tasks occupy virtually no attentional space. For most people, blinking and breathing are habitual and occur unconsciously.

Some habitual small tasks occupy a small portion of attentional space, such as scrolling through social media on a phone, reading an entertaining article, interacting with others in comments, or listening to music.

Some complex tasks may occupy the vast majority of attentional space, such as sorting out the logic of a design draft based on intricate product requirements. These tasks require complete focus to be completed successfully. If interrupted midway, the cost of resuming progress is high.

I've noticed that when I'm doing a relatively complex task (such as drafting this article), I can have background music playing without the melody disturbing my writing. In this case, my attentional space can accommodate both tasks.

However, when I'm doing an even more complex task, such as comprehending a lengthy document and needing to provide feedback, background music disrupts my thinking. As a result, I have to turn off the music and read the document in a quiet environment, carefully considering the wording of my feedback. In this situation, my attentional space can only accommodate reading the document; if I try to force another task in, I will be unable to concentrate.

To enter hyperfocus mode, one must first distinguish between these types of tasks, understand their priorities, and consciously make reasonable use of one's attentional space during a given time period.

Entering hyperfocus mode requires putting these four elements into practice:

Determine what needs to be done

Eliminate distractions

Focus attention on the task

If attention wanders, refocus it

For example, I use the time after dinner to write this article, intending to make some progress. While writing, my brain constantly considers the content to be written, and any distraction could disrupt my train of thought. I place my phone beside me and play a few familiar songs on loop to help myself concentrate on thinking and typing. My phone vibrates a few times, and I see message notifications when I pick it up – should I open them or not? Opening them would immediately satisfy my curiosity about the information, but at this moment, I know that my most important task is writing the article. Therefore, I put my phone on complete silent mode, turn off the screen, and place it face down beside me. I then return to the state of focusing on writing the article.

What would happen if I couldn't resist the curiosity and put down the article to check my phone messages? I would likely be attracted by other fresh information after reading one message, spending more time on my phone. By the time I remember that I should be writing the article, a considerable amount of time would have passed, and my previous writing train of thought would have been interrupted, requiring more time to organize my thoughts. This situation is an example of being led by surrounding information and not consciously managing one's attentional space.

Since attentional space is very limited, what would be the effect of simultaneously cramming those small, habitual tasks of life into the attentional space? According to the above categorization of tasks, they are very likely to only lead our minds into an "autopilot" mode – requiring little thought to complete these tasks. Being busy with several such tasks at once may indeed make us appear occupied, but in the end, it also leaves one feeling like they are "busily idle," seemingly accomplishing nothing. The better we manage our attention, the less time we will spend on these types of tasks.

Furthermore, when allocating attentional space, do not fill it to the brim; leave some room. Especially when we are concentrating on a highly complex task, this allows us space to reflect on our methods and constantly check whether we are heading in the right direction. When our minds are crammed full, with no extra thinking space, we become unable to clearly judge at any time whether what we are doing is what we should be doing, and we will also feel very exhausted.

Scatterfocus

When a person enters scatterfocus mode, their thinking enters a wandering state. This part discusses how to be more creative while continuing to manage attention and thoughts.

The author introduces three modes of thought wandering:

Capture mode: Let our minds roam freely and record the ideas that emerge.

Problem-crunching mode: Roughly consider a problem in our minds and let our thoughts wander around it.

Habitual mode: Do a simple task and record the ideas and plans that arise in our minds while doing it.

I have experienced all three modes. Sometimes, when I really want to draw but am unsure what to draw, I randomly browse pictures online and casually sketch all the ideas that come to mind until I find an angle I like. Occasionally, when I have difficulty falling asleep and my mind is jumbled with thoughts about the day, I suddenly think of a connection that can advance a project or a contact who can help solve a problem. In these moments, I immediately grab my phone to make a note, after which I can quickly fall asleep with peace of mind. While washing dishes after a meal, I stare at the water flowing over the plates, and my mind wanders to things I usually don't have time to consider, like adding a few more plants to the house. I make a note to buy them later.

These wandering thoughts are not aimless; we consciously let them roam and then capture those flashes of inspiration. This wandering can help alleviate the fatigue caused by concentrated focus, conserving energy to face more important tasks later.